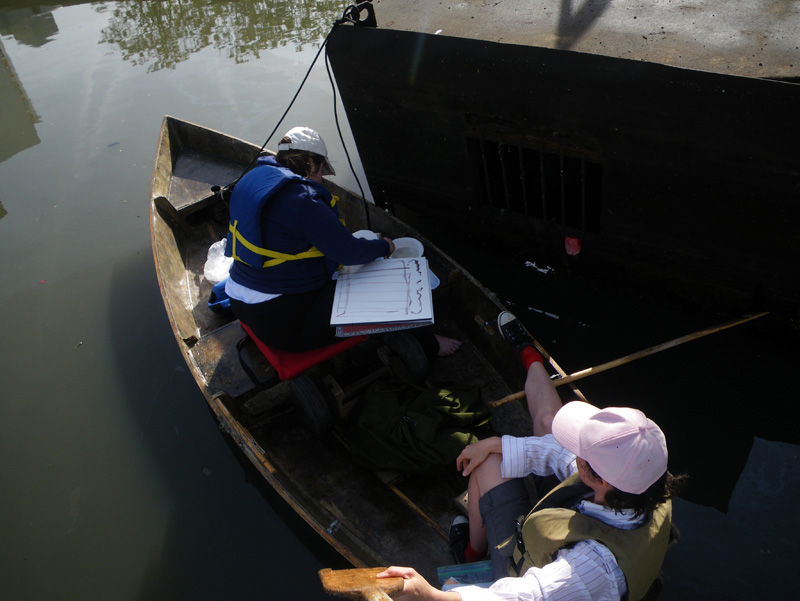

When I met Caroline and Sarah at the end of Java Street on Friday morning,

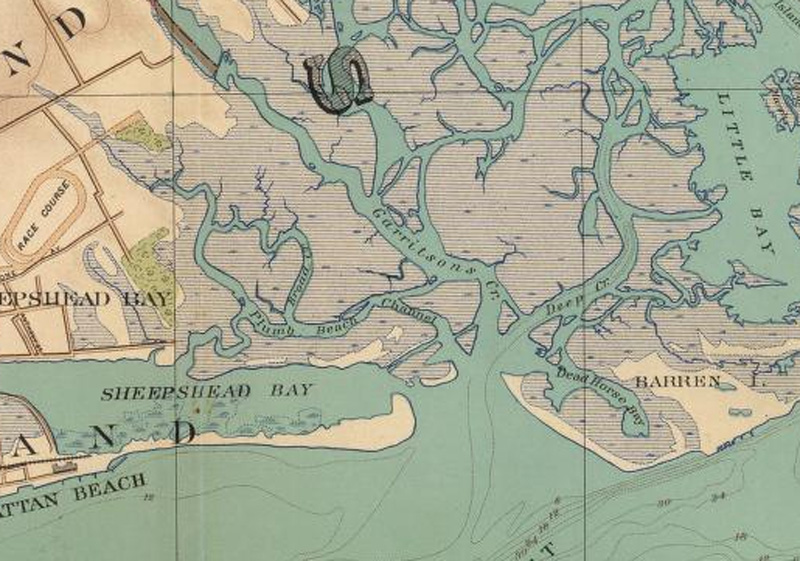

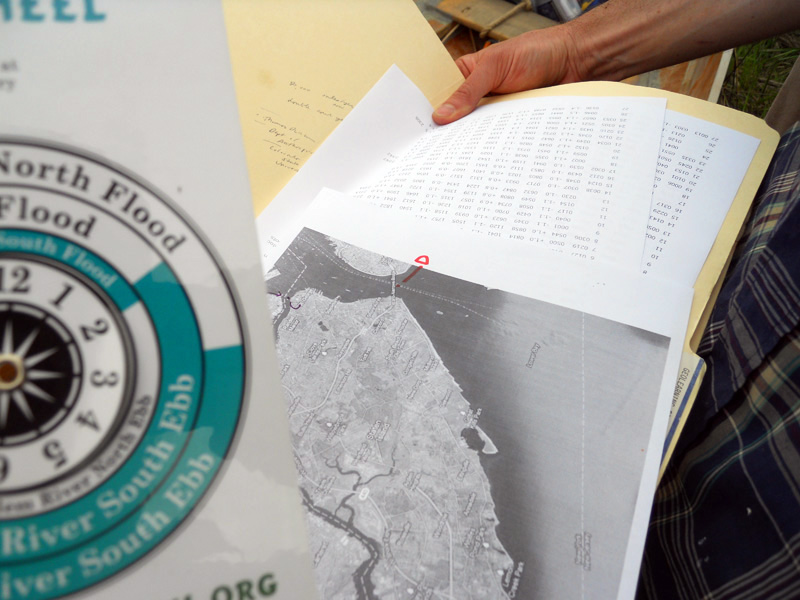

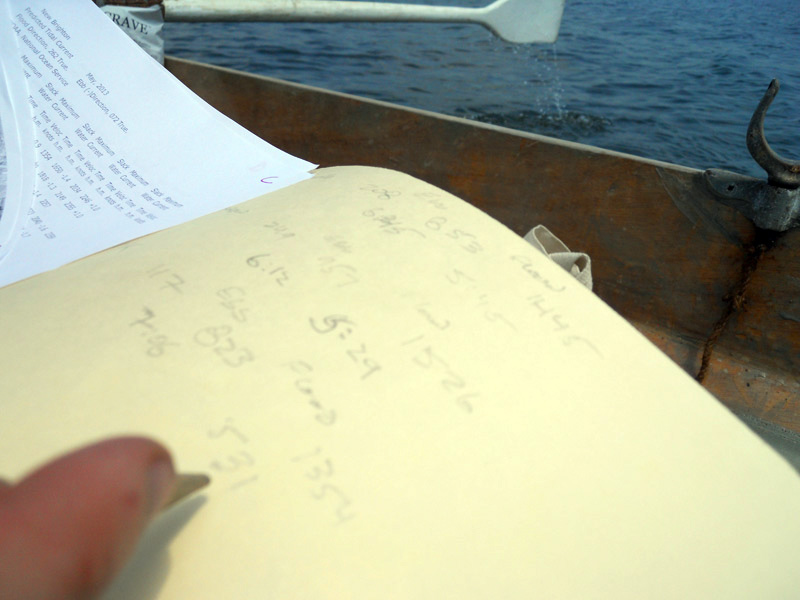

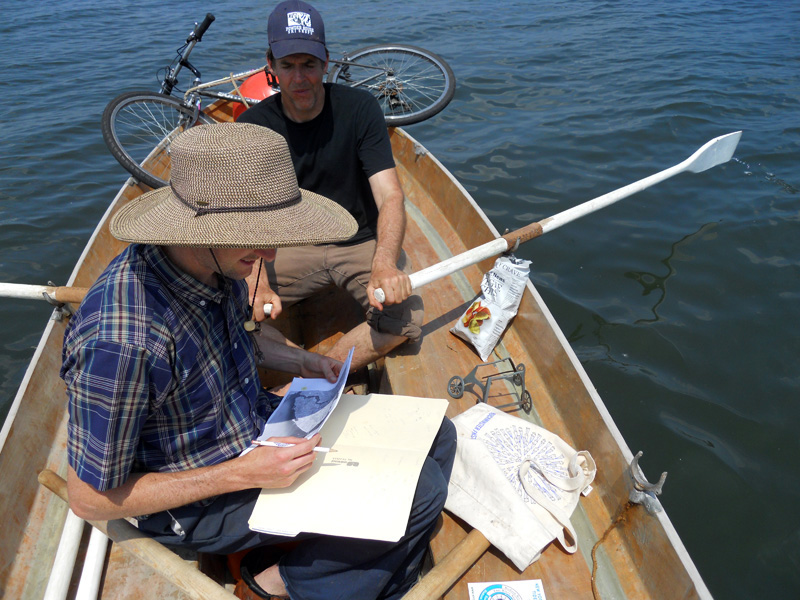

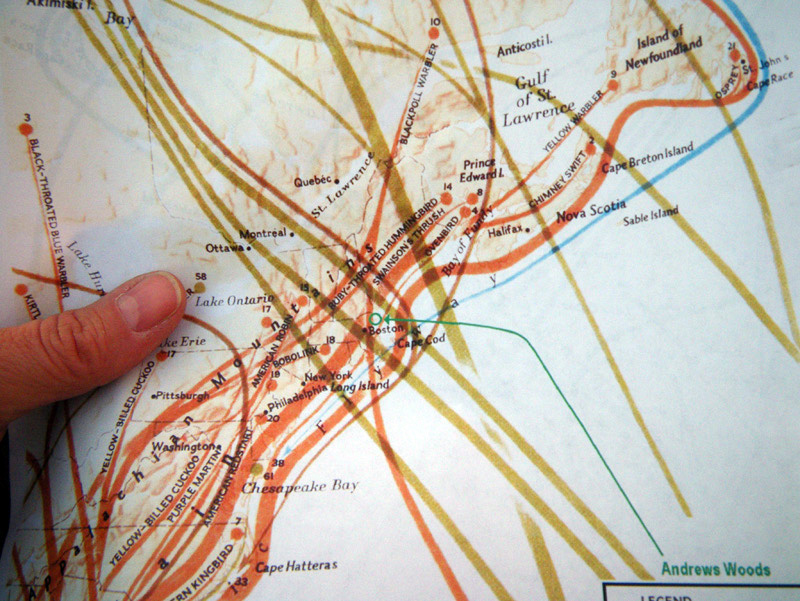

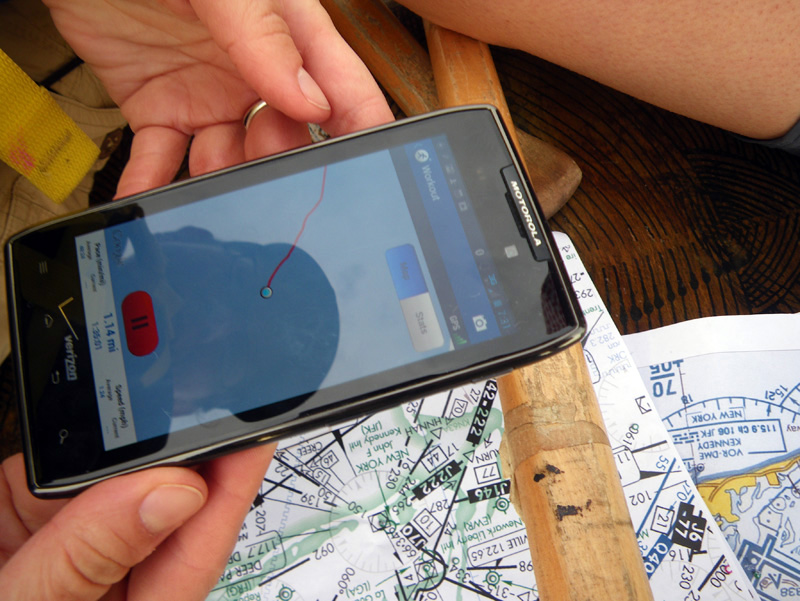

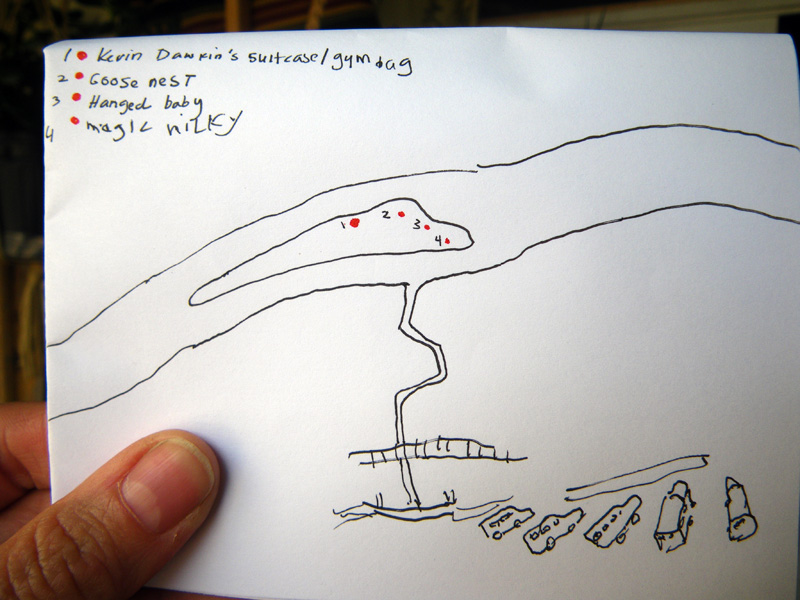

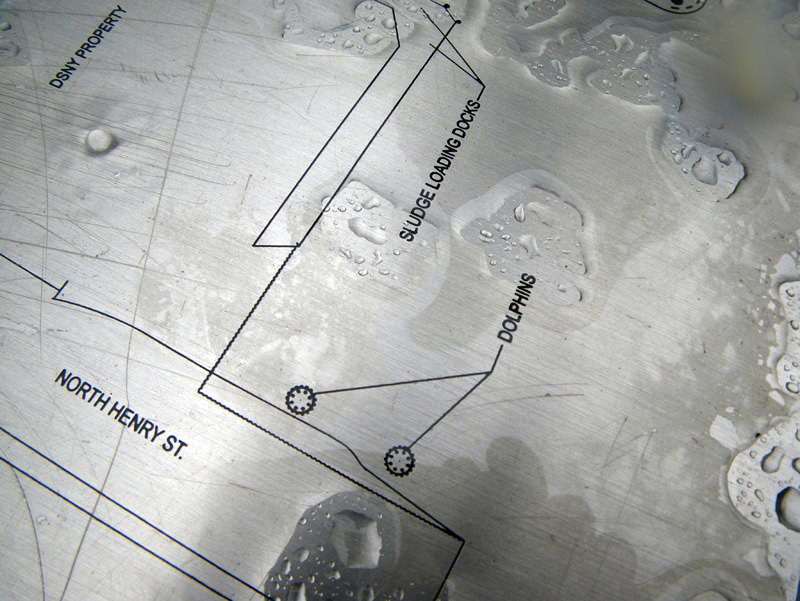

we didn’t have much of a map,

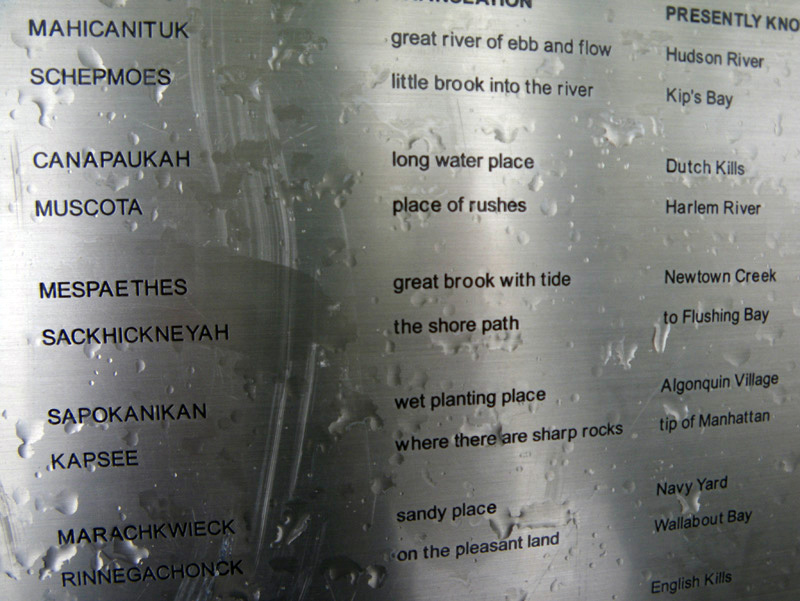

just a plan to see some of the prettiest coastline in New York City.

We set our date months ago, and it couldn’t have fallen on a prettier day.

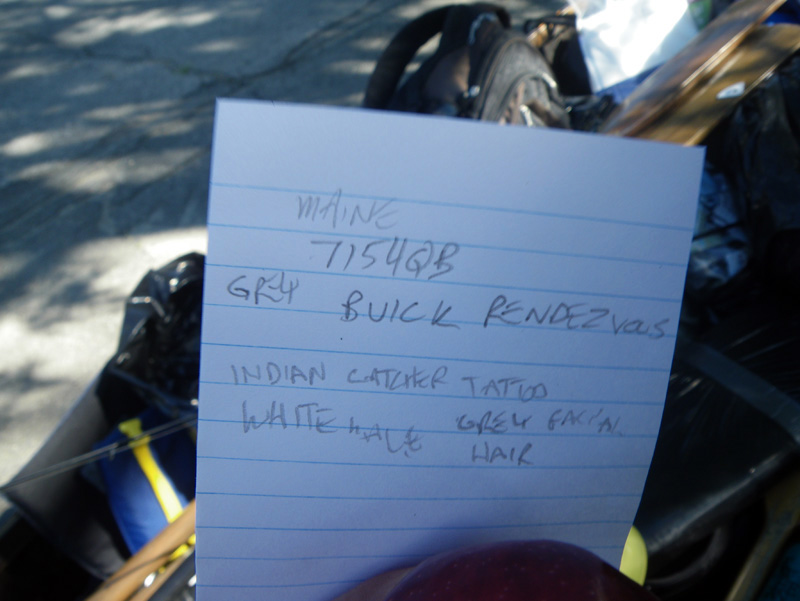

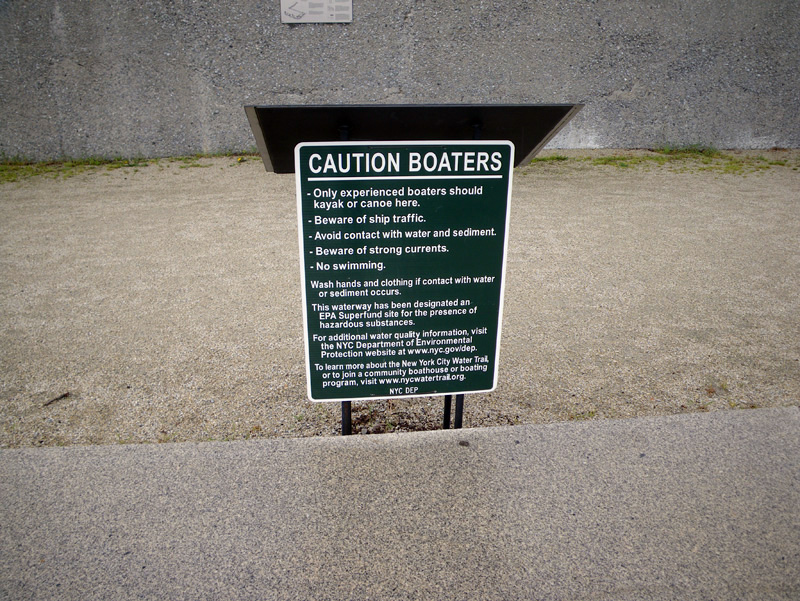

I knew that Sarah was a little apprehensive about the water,

so I paid careful attention to the traffic.

But when she calmly watched a huge DEP ship roll past,

I knew we it would be smooth sailing.

“New York looks great from the water,” said Sarah. “just like it does on television!”

Our first stop was Roosevelt Island.

Sarah had never been there before, so it seemed fitting to come by water.

We were caught landing by park employees. “The park is closed!” they said. “Stay on the other side of the fence!”

When you come by water, it’s hard to tell which side of the fence is ‘other’,

so we wandered happily between the fences for a while, thinking that our blue life jackets made us look like park employees anyhow.

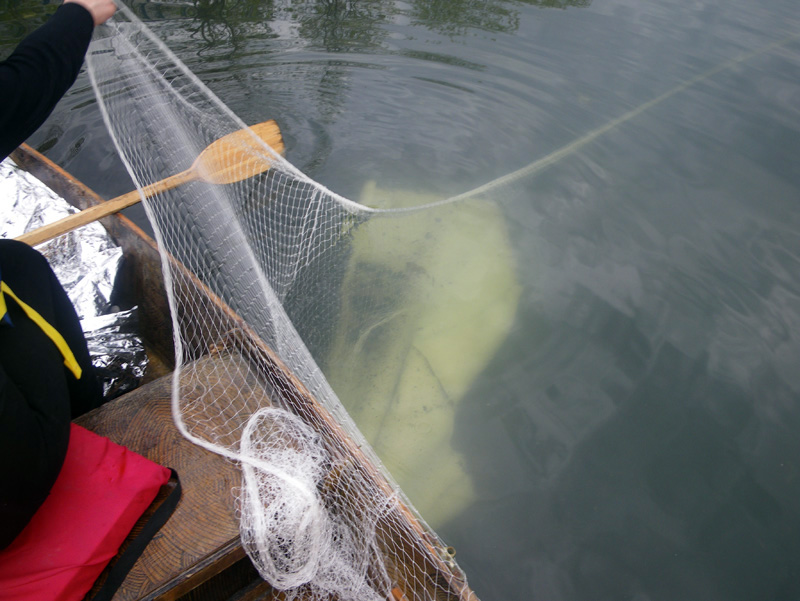

Soon the water called us back,

and we headed up the East River with the incoming tide.

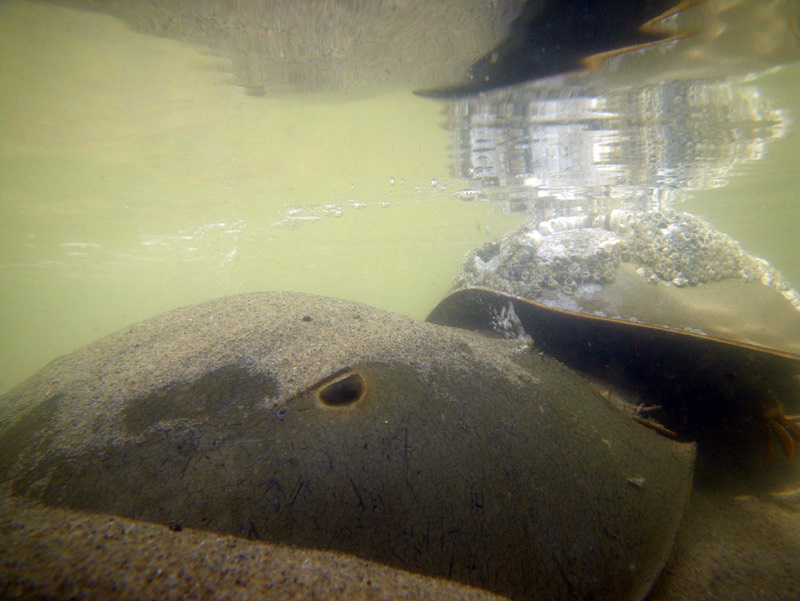

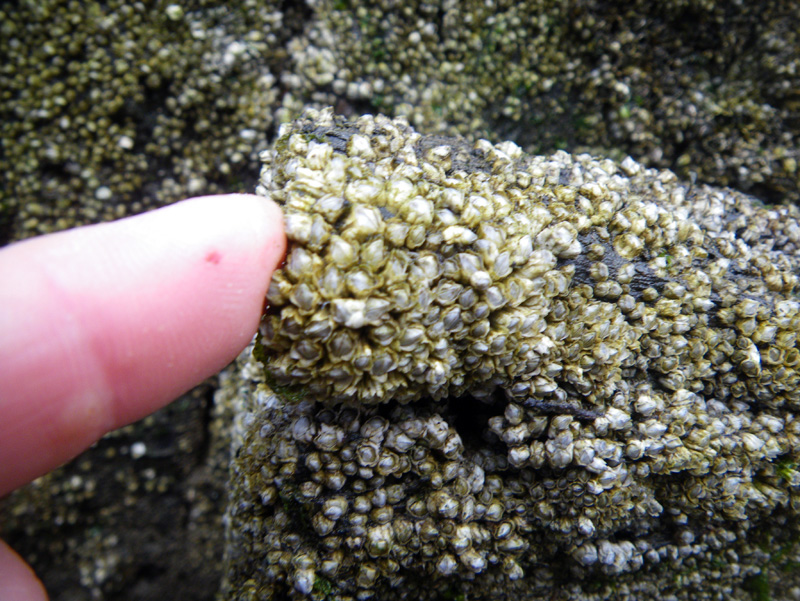

Our next destination was Milrock Island, an abandoned stretch of land,

just past the northern tip of Roosevelt Island.

It was man-made in 1885 from rocks cleared out of the Hell’s Gate shipping channel.

“An island’s island.” said Caroline.

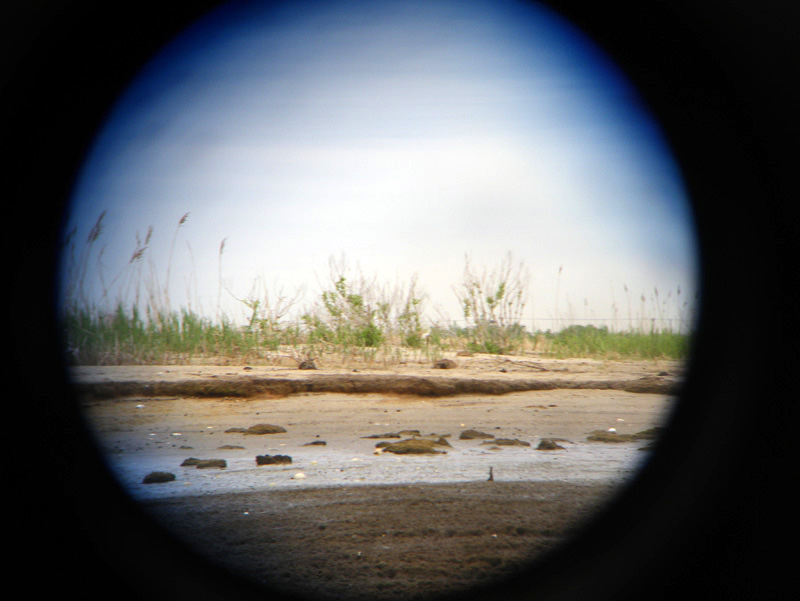

There is a story in ‘Other Islands of New York City’ about a group of school children who landed on the island in the 1950’s and were attacked by rats.

We saw one, but I was so excited that I fumbled with my camera and didn’t get its picture.

The rat was of a strange variety, almost like a nutria, or an islandized descendant of the children-eating ones…

living just on bones.

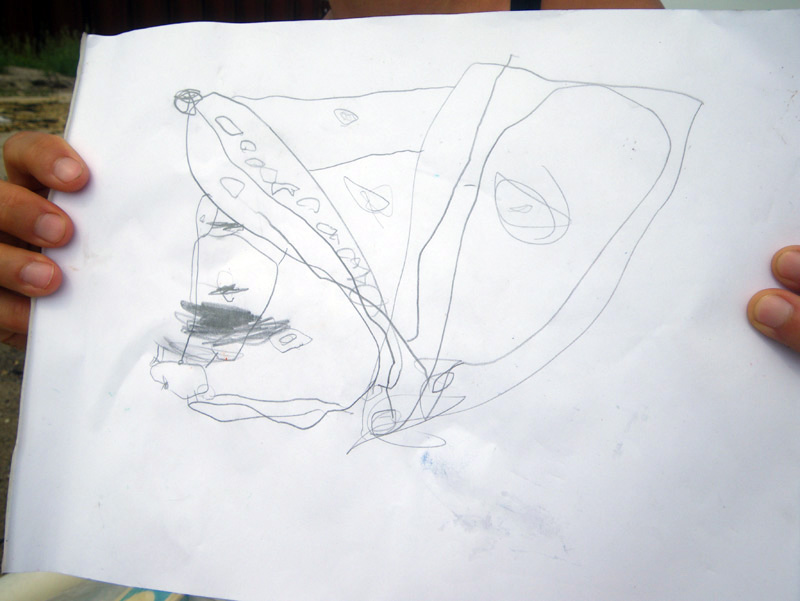

I told Sarah and Caroline about a video I want to make where a group of women survive armageddon by living on islands in New York City.

Caroline told us about the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, an all-female commune established to protest nuclear weapons in 1981.

The protest lasted 19 years, and helped bring about legislation that removed Cruise Missiles from the Greenham Common Airbase.

Caroline said that the camp was divided into skill groups. “There were sections for artists, cooks, and a whole group of women who’s job it was just to interact with the police.”

“I want to be in the group that deals with the cops.” said Sarah.

I figured we would all just be in the art section, but actually, Sarah would be great on the front lines.

She is the director of an art residency where I worked this summer, and her demeanor is perfect;

fair, strong, and protective of her brood.

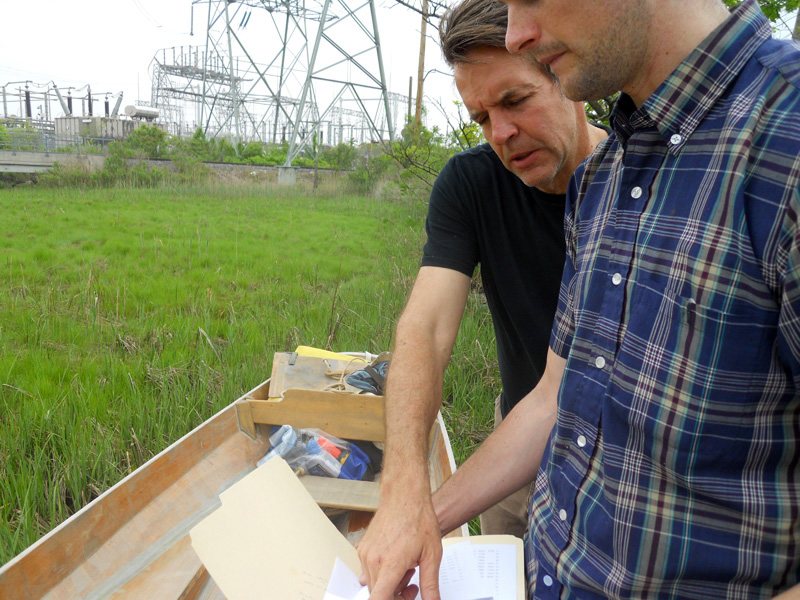

Meanwhile, we were coming up to a spot that Caroline wanted to check out.

From the street it looks like a little brick castle, nestled between a bridge and power plant. This would be a perfect home for Caroline’s next community land trust experiment.

“You can’t really get to it from here.” said Caroline.

“We’ll have to come back by land.” I said.

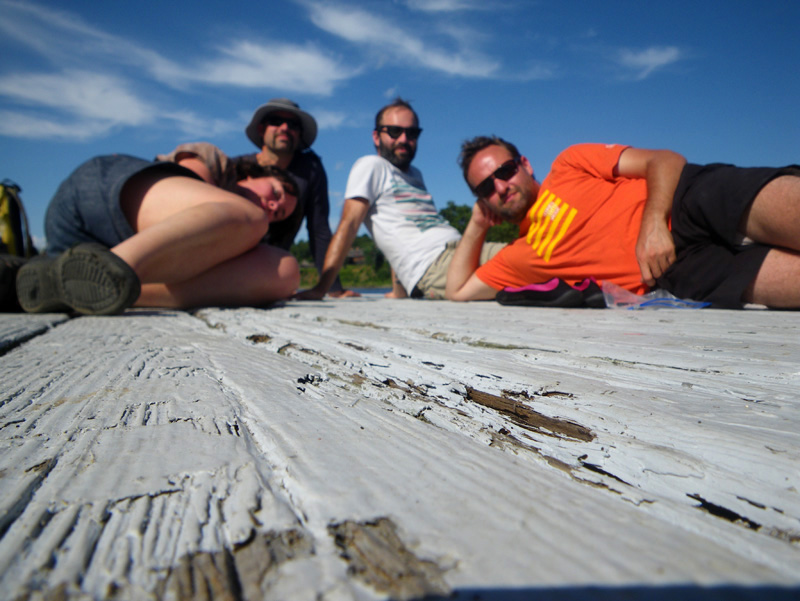

We pulled up at Anable Basin,

to find something to eat.

They weren’t serving sausages this early in the morning, but there was plenty of beer.

We talked for almost an hour, hatching a plan to redirect the mission of ‘Kickstarter’ to actually change the world.

“You see,” said Caroline, “the system can’t change if people still want private property.”

“Real change can only come with public ownership; a return to the commons.”

Caroline doesn’t just say stuff like that either, her life’s work is about it.

With projects like Trade School and OurGoods, she has worked to put her beliefs into practice on a large scale.

The tide was moving fast now and we were being delivered back to our launching point,

past a group of cormorants,

past the Huron Street Piers.

“Be sure and tell us when you make your video about the women who survive the end of the world!” said Caroline and Sarah.

“We want to be in it!”

“You already are.” I thought.