In May, Jeff Williams and I were invited by Dylan Gauthier and Kendra Sullivan to participate in their a residency at the Cape Cod Modern House Trust, a non-profit foundation created to save and repurpose a group of historic structures as “platforms for creativity, scholarship and public access.”

(Serge, Barbara, Ivan, and Peter Chermayeff at their new home on Slough Pond, 1944)

The houses were built on the Cape in the mid 20th century by architects like Marcel Breuer, Serge Chermayeff and Paul Weidlinger.

(Weidlinger House under restoration, 2013)

When the Cape Cod National Seashore was created in 1961, some of these houses became part of the park. Most of them had been abandoned for years, and were slated for demolition,

(Hatch Cottage, designed by Jack Hall in 1960)

but the parks department didn’t rip them up right away. As an archeological site, the Cape Cod National Seashore concerns itself with more than just the natural landscape.

The park has collected and cataloged thousands of artifacts like these drawers of arrowheads,

scrimshaw,

the pelt of a giant polar bear.

Houses are more expensive to maintain than these artifacts (Bill Burke gave us a behind the scenes peak into the park’s historic collection), so the Cape Cod Modern House Trust raises money for their upkeep and public programming.

Talking with Bill about the Discovery Center’s vast collection made us curious about some of the other intersections of artifact and landscape on the Cape.

The evening before, we stood on a bridge as the tide went out and watched a giant sunfish struggling in the marsh.

We went to find his body at low tide, and realized how far he’d actually been from safety.

A man fishing from the bridge told us that he had seed quite a few wash up this year. The cape can leave animals miles from open water in just a few minutes.

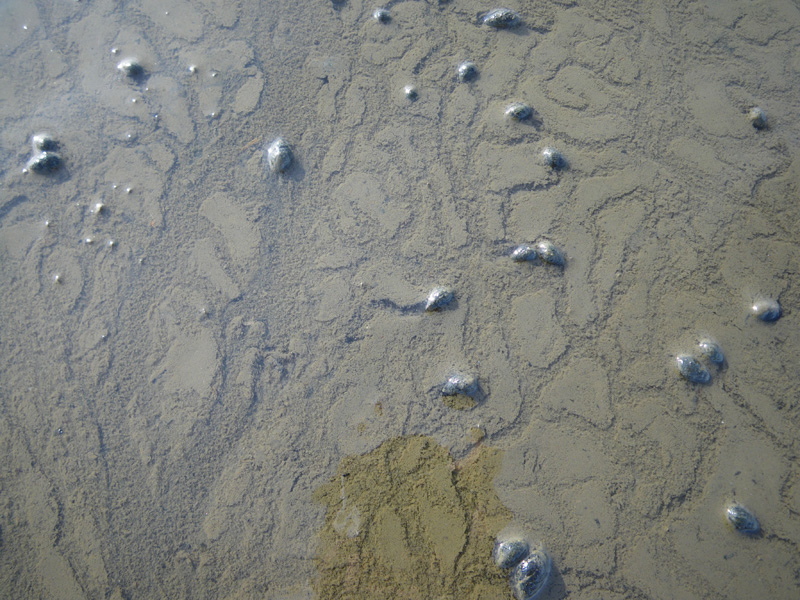

As we walked away, the receding tide made a million tiny rivers,

with unknown numbers of living things stranded in their ebb.

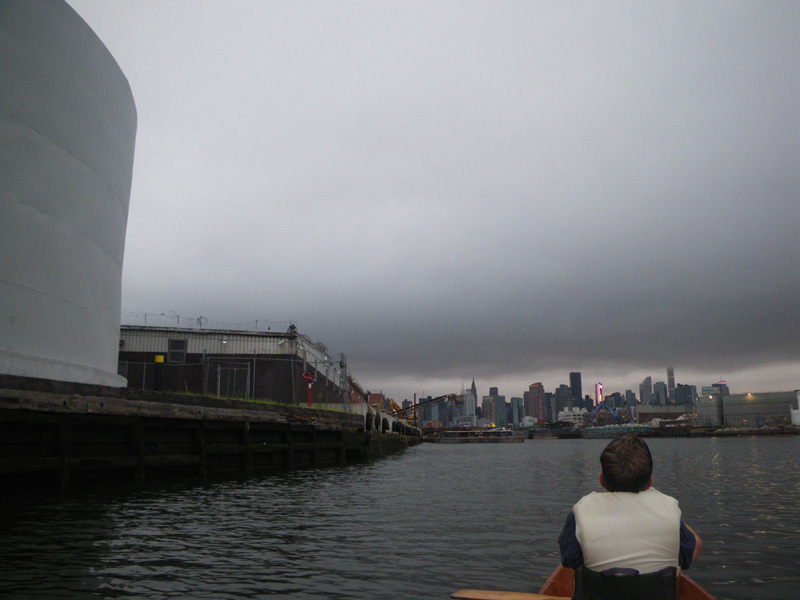

We paddled back out to a strange discovery;

another sunfish, recently deceased, its giant body floating just below the surface.

The large numbers of sunfish stranded in the Cape this year might be due to climate change. Warm water, late in the season prevents the fish from migrating. A sudden cold current can change the amount of dissolved oxygen in the water. The sunfish basically suffocate in the cold.

At least that’s what the fisherman told us the night before.

“It was my favorite fish.” said Jeff.

He was referring to another giant that lived at the Monterey Bay Aquarium in 1980s. The aquarium used to catch young sunfish and release them back into the wild after a few years. But this one, Jeffs favorite, had grown too big to move. Seven feet tall and weighing over 3000 pounds, the fish had plied the waters of the Open Sea™ exhibit for most of Jeff’s childhood.

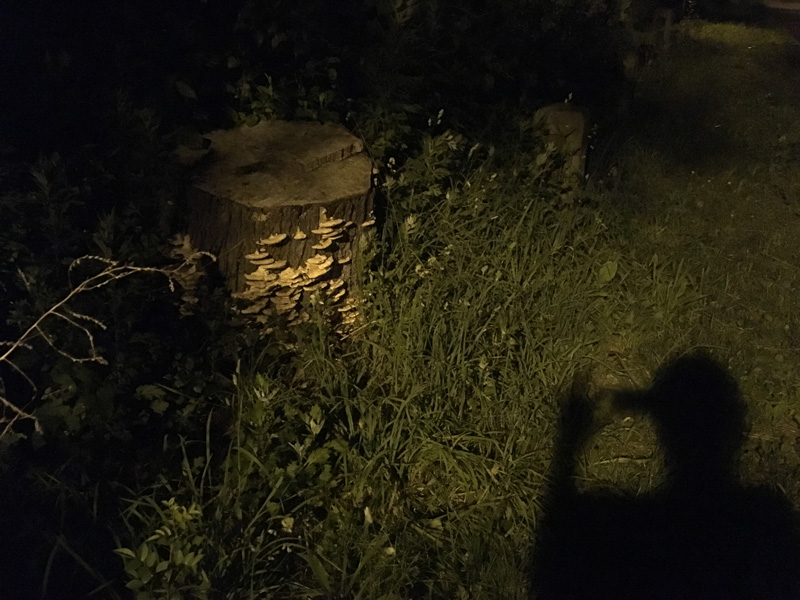

We continued on land to find more artifacts.

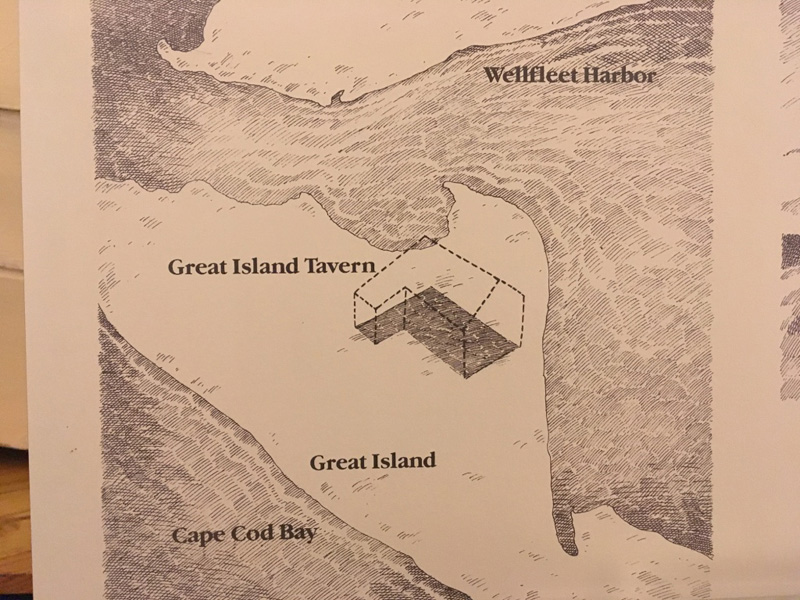

Excavations in the 1960’s revealed thousands of pipe stems and drinking vessels here on Great Island, the site of a 17th century Tavern that, evidently, did not haul away its trash.

There’s not much evidence of the tavern now, except for a perfect view of both the ocean and the bay.

All the trash we found was from the wrong century.

When does garbage become archeology anyway? 300 years? 30 years? If the effects of human beings can be found on everything, then isn’t every object a mix of natural and cultural, if only by degrees?

If the unintended consequences of development are considered cultural artifacts, then this unassuming little bridge is a prolific cultural producer.

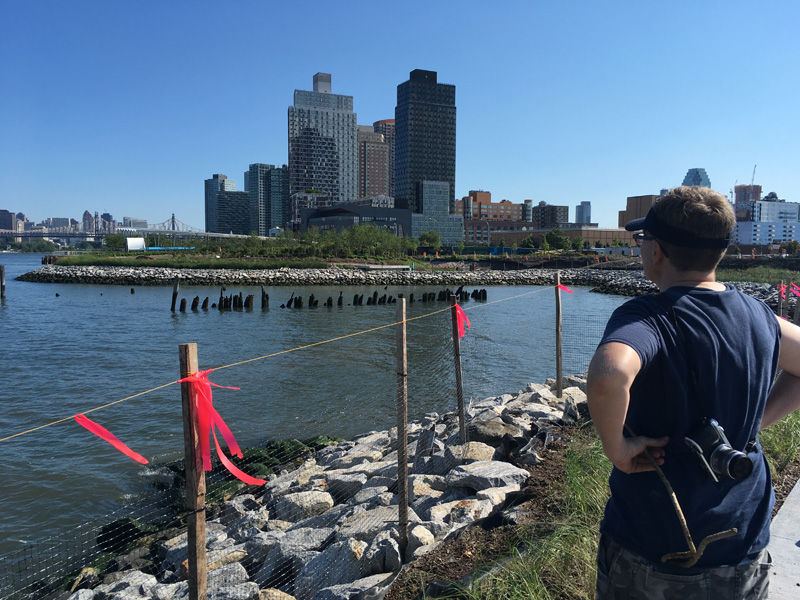

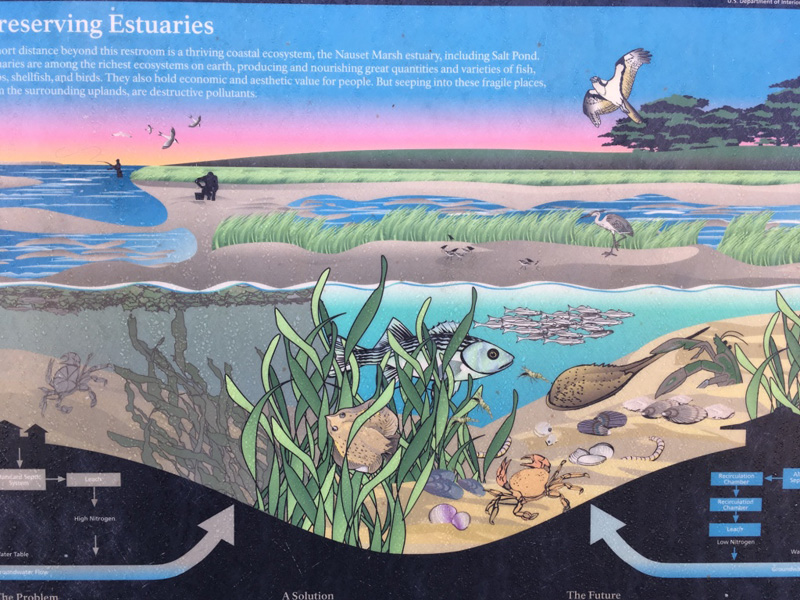

The Herring River Dike was built in 1909 to control water in the upper estuary. Like similar projects all along the eastern seaboard, it opened acres of land for development and reduced the size of the saltwater marsh.

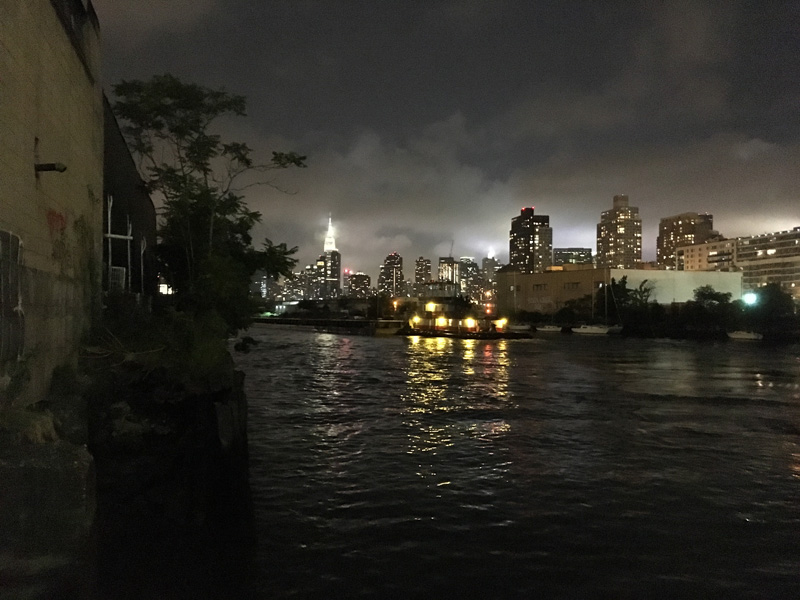

When the tide is high on the ocean side,

only a small amount of water comes through the dike, reducing the tidal range in the upper estuary.

After hearing about the Herring River dike and the problems that it created for the estuary, I wondered if we would even be able to tell the difference.

The two sides of this placard at that Cape Cod Visitor Information Center look similar to me – especially above the waterline.

But there were some differences that were evident, even to a layman.

Our boat wound through acres and acres of Phragmites australias, an invasive species that seems to thrive in polluted environments.

And another plant that I didn’t recognize seemed to be doing VERY well over here on the impacted side of the dike.

“Toxic lettuce” Jeff called it.

As the river narrowed, the Phragmites gave way to taller trees, and the shore hummed with bugs and birds.

Most of this will die when the salt water tides are allowed back to their pre-1909 levels.

We saw the monitoring equipment from that the National Seashore’s Natural Resource Management & Science division.

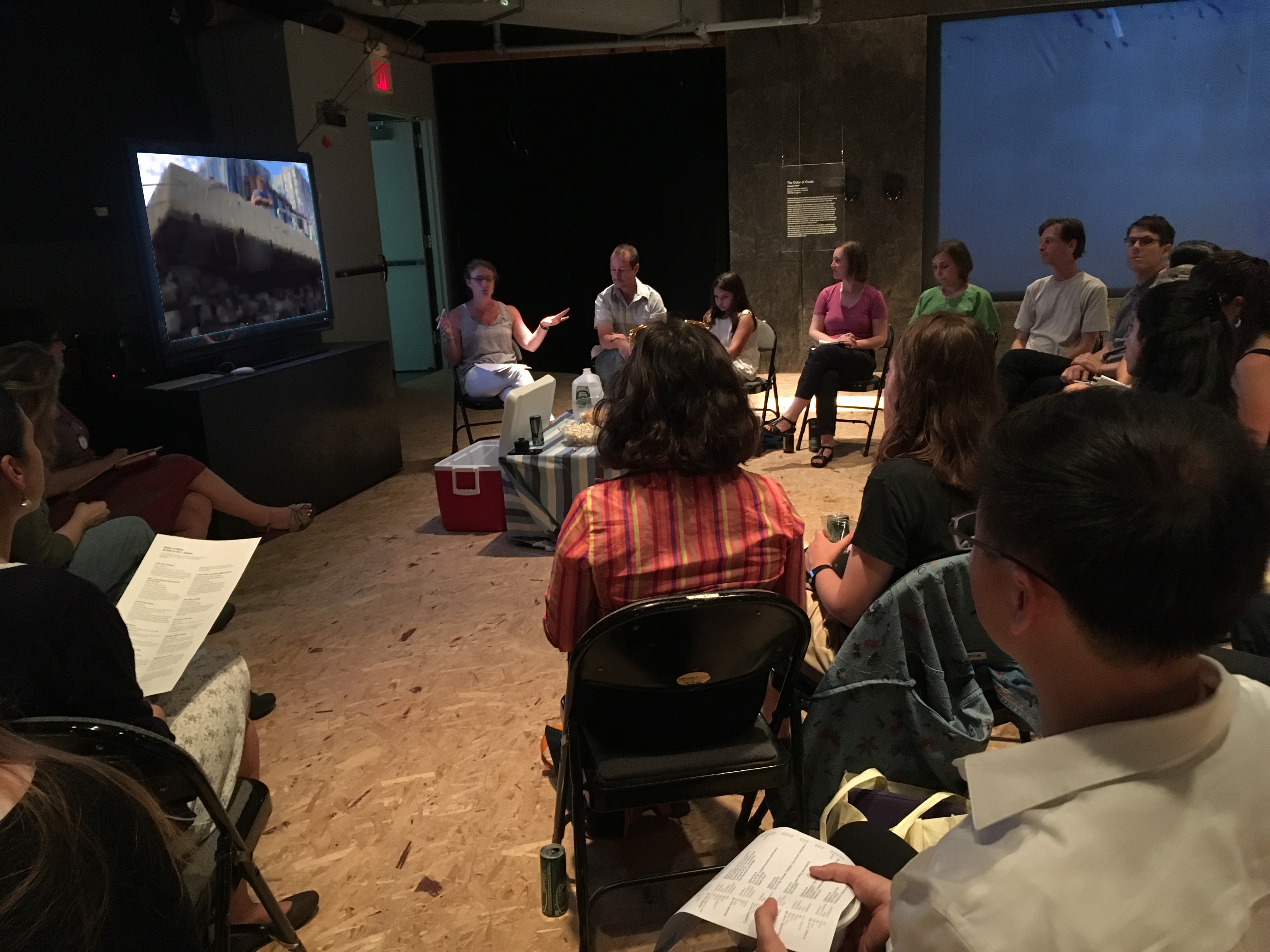

The day before Sofia Fox, the Division’s Aquatic Ecologist sat down with me to tell me about the Herring River restoration project,

and the complex landscape of interests that surround estuarine recovery and change in Wellfleet.

The herring river narrowed down to just one pipe, and crossed under a sand road.

We passed a woman walking, and told her that we were paddling up the Herring River.

“They want to turn this back into a marsh.” she said, glancing wistfully back down her sandy path.

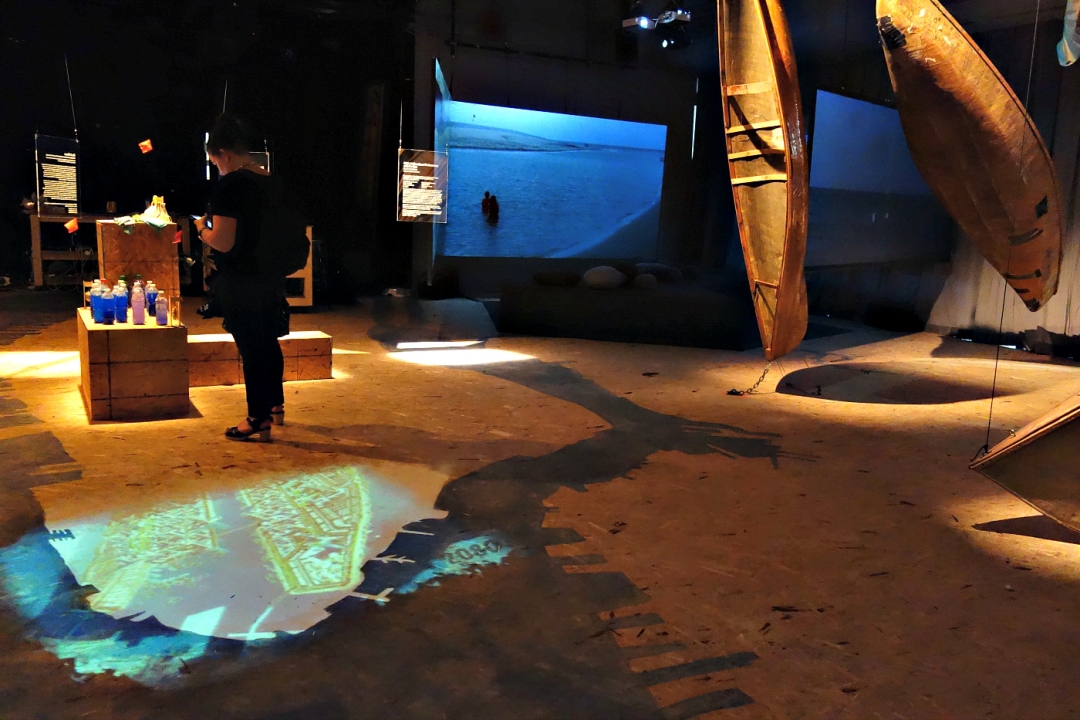

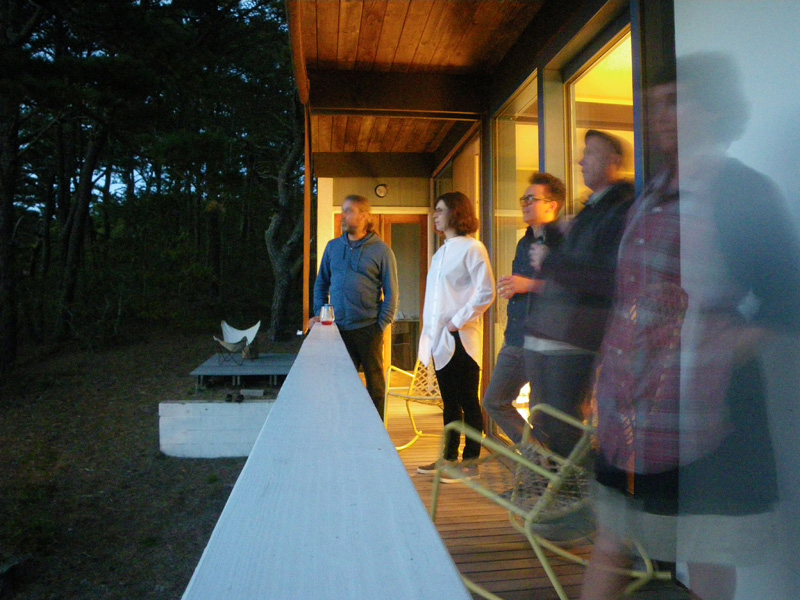

Later that night we watched the sun set from the deck of Weildinger house, with Peter McMahon, the founding director of the Cape Cod Modern House Trust, and Dylan Gauthier and Kendra Sullivan, artists and curators of the Art/Science residency.

That night I understood the importance Peter’s mission to “fill the houses with conversation” like the ones that were so important on the cape in the 1950s.

It felt like we had bridged some gap in time.

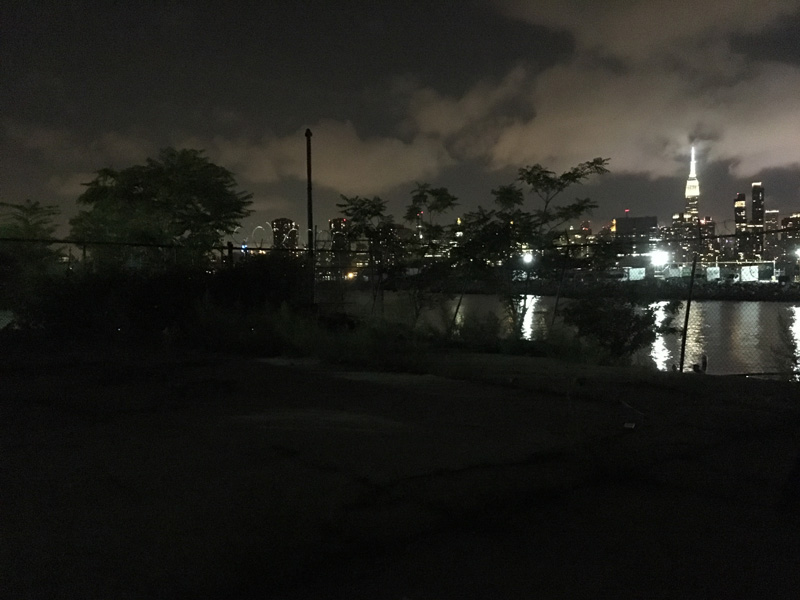

The next morning a dense fog settled over the pond.

I pulled the boat out, traveling from one pond to the next; Gull, Higgins, Williams, Herring …

The ponds are glacier made, spring fed, and supply freshwater to the Herring River Estuary. It would be possible to go from here to where we ended our paddle yesterday, clear across the cape,

but I didn’t go that way.

I paddled to the middle of the pond, until I couldn’t see the bank on either side.