In early November, I took a trip into the Meadowlands with Robert Sullivan and David Diehl.

We were heading for Sky Mound, Nancy Holt’s monumental and yet unfinished earthwork.

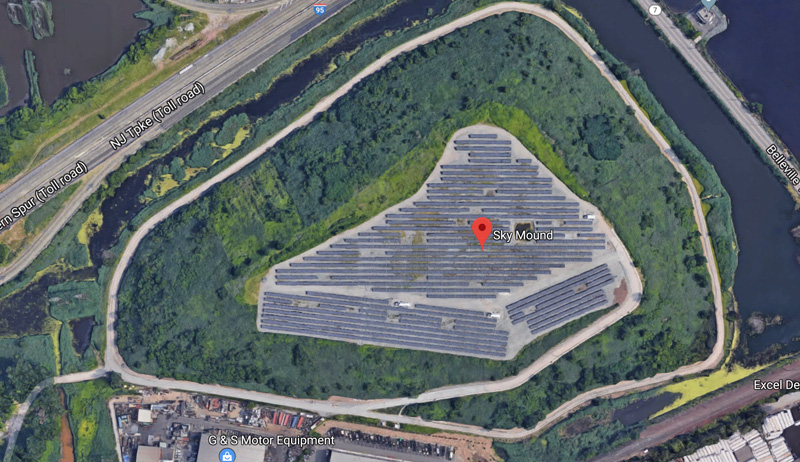

Holt began the project in 1988 with the Hackensack Meadowlands Development Commission, to convert a 57-acre landfill into a public park with giant earth pyramids structured to align with celestial events. The artwork would also make use of garbage underneath the mounds, pipes emitting methane could be a source of power for the surrounding neighborhoods.

After enclosing the dump, the project was put on hold, and from satellite photos, we could see that the Sky Mound was now a giant solar array.

Robert pointed out that solar panels are form of celestial alignment and they give power to the surrounding neighborhoods, in a weird displacement of the original plans for Sky Mound.

Also, Sky Mound still wasn’t a public park and we were having a hard time getting anywhere close to the landfill.

Berms of raised earth surrounded the area.

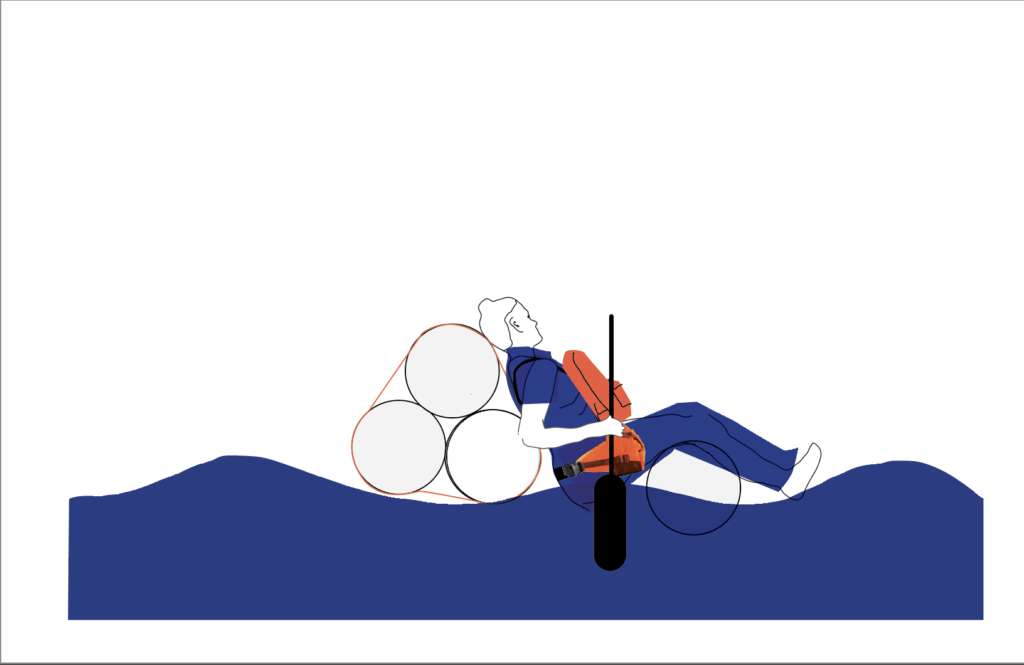

“We just have to haul the boat over one of these.†I said.

Robert kept reminding us about people who had been arrested for doing this very sort of thing.

I was worried about getting our feet wet. Climbing in and out of the boat an extra four times was tricky in cold weather, and everything was going so well, so far.

So we took a vote,

and hauled the boat over the berm.

We could see trucks inching along the New Jersey Turnpike a hundred feet above.

Robert described how an engineering development in the 1950s allowed the bridge to cut straight across the Meadowlands. Using suction caissons “they could draw a line on the map and make a road there, they no longer had to worry about the marsh.â€

The land under the turnpike still looked like marsh, but a barely submerged berm of gravel separated us from the Sky Mound.

Not wanting to risk another portage, we picked our way along on the deep side of the enclosure.

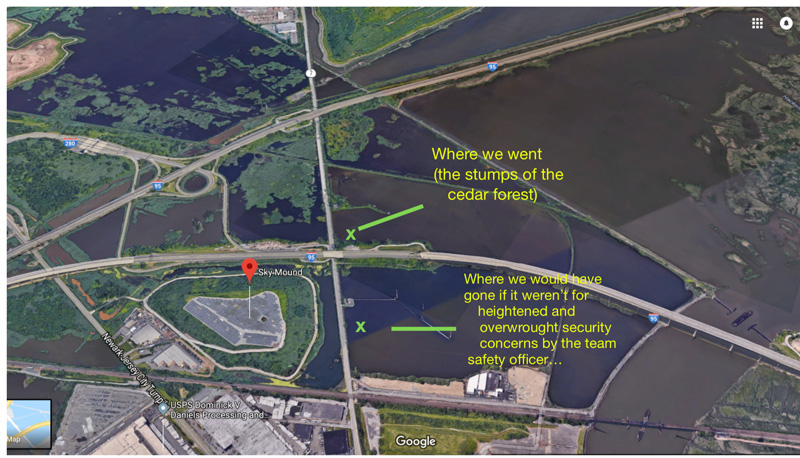

Robert sent us a map the next day to show how close we had been to the Sky Mound.

It was difficult to give up and turn around. I had imagined walking across Nancy Holt’s earthwork, and even as a symbol the site had a monumental gravity,

but we hadn’t come to the Meadowlands just to see the Sky Mound.

This year marked the 20th anniversary of David and Robert’s boat trip into the Meadowlands when Robert was researching for his famous book.

It was amazing to be here with Robert who had contemplated and written about everything that we were seeing;

a radio antenna that broadcast the first Frank Sinatra recordings,

stumps of an old cedar forrest,

it was like the best parts of reading, when your whole being dissolves inside the book,

but even better because now I could hear about all these other parts,

details about David and Robert growing up in New Jersey, about things that happened on their trip, and things they thought about today.

“It’s weird to be back in a place and remember things that you didn’t even know you forgot.†said Robert.

I imagined the boat ride as a kind of interview, where instead of asking questions, we let the landscape float by and ask its own questions,

or not questions exactly, but suggestions,

memories and future memories, of a million people and things.

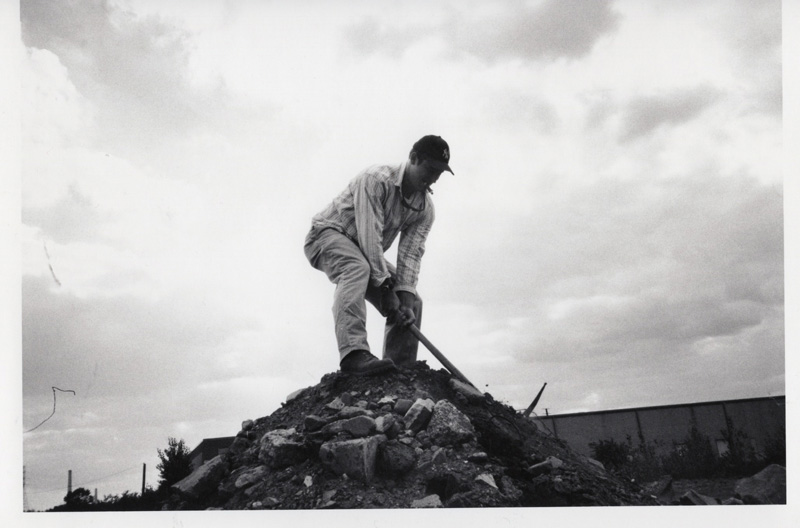

The next day Robert sent us some old pictures from that first trip 20 years ago,

David digging up chunks of the old Penn Station,

Robert taking notes,

and David’s collage that looked like it could have been made 20 years ago or yesterday.