Elizabeth Rush and I were planning a trip to the Fresh Kills Landfill to coincide with an article she was writing about the waste stream in New York,

but after Hurricane Sandy devastated Staten Island, we wondered if we should make the trip at all.

“No one has been talking about how the landfill faired in the storm,” said Liz, “I think now might be a good time to check it out.”

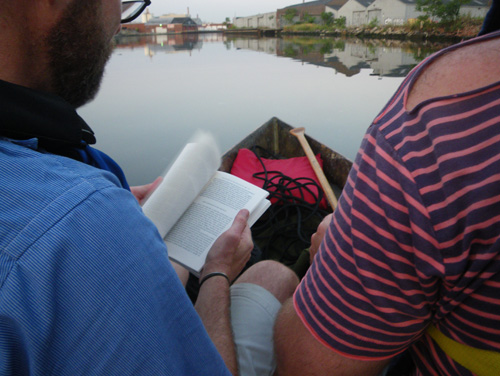

So at sunrise on November 4th, we set out from the boat graveyard to see what was left of Fresh Kills.

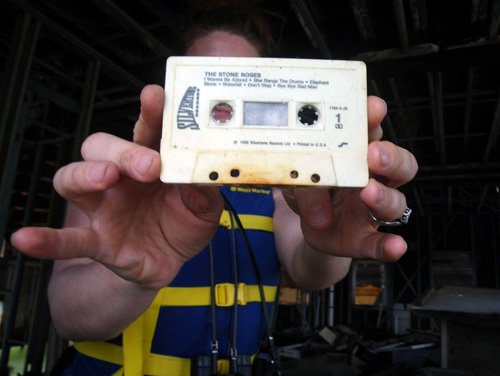

It seemed fitting, anyway, to wrap up a Tide and Current Taxi season that had been mostly about garbage,

the week after Hurricane Sandy reduced parts of New York to floating rubble,

by paddling to what was once the largest landfill in the world.

The first thing that we encountered as we floated toward the Kills, was a huge, retaining fence encircling the mound.

“It’s meant to catch trash that might have fallen into the water while the barges were being unloaded.” said Liz.

We started to notice though, that there was more trash on our side of the fence than on the landfill side.

We saw debris stuck in the fence all the way to the top.

At some point during the hurricane, water must have breached the wall.

As we entered the Fresh Kills Estuary, Liz was suprised to see large barges full of garbage.

I thought that was what we were here to see. But Liz explained that there shouldn’t be much trash here at all. Other than a small transfer station somewhere inside the park, the Fresh Kills Landfill has been capped for years.

“Maybe there is extra trash because of the Hurricane.” I thought.

As we moved upstream, we started to see some real damge from the storm.

Sections of floating barricade were thrown over the retaining wall like soggy pillows,

and a crumpled dry-dock lay creaking on its barge.

It was strange that the damage seemed concentrated this far upstream, and we tried to imagine the path and force of the water as it moved through the area.

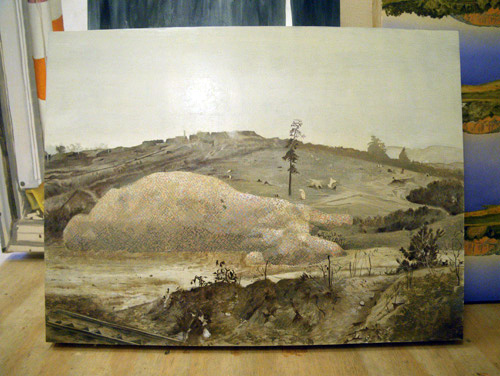

For the most part, the land seemed quiet and unaffected.

We were about a mile into the old dumping site now,

and the estuary stretched out before us like a scroll.

We saw deer running along the embankment, and osprey circled above.

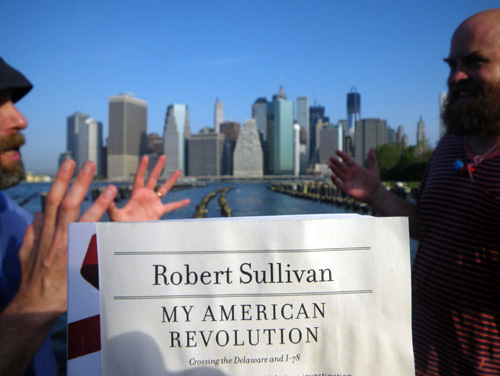

Liz knows a lot about the site from her research.

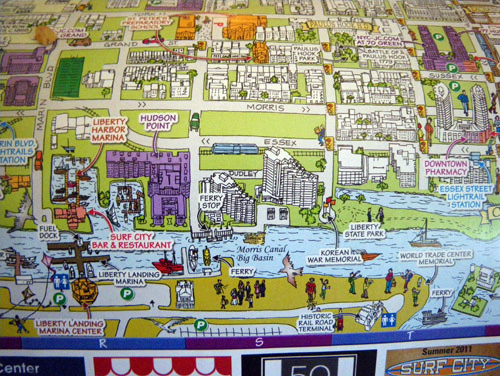

The city has plans to turn the former landfill into a giant public park.

I found this optimistic rendering from an NYC Parks website that describes the future development as “a productive and beautiful cultural destination.”

That is not so different than what it is now, depending on your ideas about culture and beauty.

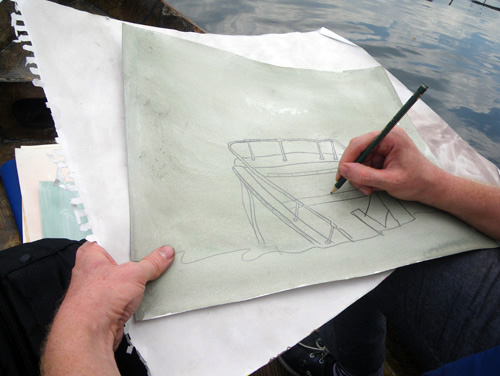

We decided to stop and have a closer look at one of  the mounds.

About 15 feet from the shoreline, we walked along a dense bank of grass shaft and debris.

We realized we were walking on a massive phragmites drift that was deposited here during the hurricane. “The new high-water mark.” said Liz.

However interesting, this was no place for lunch. Liz wanted to hike up one of the mounds to a spot where we could see out,

so we tied up the boat,

and jumped up on the trash barges.

It was amazing being on top of the barges.

Huge nets were draped across like circus tents to bind the trash.

“What do you think this is,” asked Liz, “a day of trash? A month?”

It made my head spin to think about the volumes of garbage coming in every day.

We found a place to hop from the docks onto the mound.

“This is mound 4,” said Liz, “where the twin towers are.”

I wasn’t sure what she was talking about at first, but then I remembered.

After September 11th, the rubble from the World Trade Center was brought here, sorted through, and buried.

Now a huge memorial is planned for the site.

We ate our lunch on mound 4 and watched as osprey circled and dove around us, hunting for their own lunch.

“What time do you think it is?” I asked Liz.

We had been up hours before sunrise and I suddenly felt like the day was slipping by.

In her study of Fresh Kills, Liz has been talking a lot to Mierle Laderman Ukeles. She is the official artist-in-residence of the Fresh Kills Park, commissioned by the Percent for Art Program.

When we were having reservations about making our trip, Liz asked Mierle what she thought.

Mierle was very worried about how the landfill had faired in the storm. “If the debris just got washed away, that would truly be tragic,” she said, “please tell me what you see and find.”

Now Liz could report that the landfill did not get washed away in Hurricane Sandy.

If anything, it grew.

We headed back to shore.

We had one more thing to do on Staten Island.

We packed up and headed to the east coast of the island, the part hardest hit in the hurricane.

I had seen plenty of pictures of this on the news so I didn’t take any new ones, but as we drove across the island we saw a drastic change in the state of things. Destroyed homes and piles of debris, families filling dumpsters with their own wrecked stuff,

and everywhere, the rerouted New York City Marathon athletes were helping out; running with supplies from house to house and lending a hand to clear waste.

We brought our load of food and supplies to an assistance center at Miller Field,

and made our way through the stalled lines of traffic back to Brooklyn.