Some of the most interesting things along the Tiber River are right around the Isola Tiberina in Rome’s historic center.

This is the Pons Fabricius: the oldest working bridge in Rome. It has been used, basically in the same state, since 62 BC.

And here remains the marble prow of a sculpted Roman ship. The whole island was once carved into the shape of a boat.

The ponte Rotto is the very oldest Roman stone bridge: 179 BC.

And here is something very old too: the outfall of the Cloaca Maxima. It is the oldest sewer in the world. It may have been started as early as 600 BC, and the modern Roman sewer system still runs through part of it.

Under the arch of the Cloaca’s outfall there is just a little cave, with no entrance into what remains of the sewer. But a little further down there is another hole.

Matt Hural, an architect at the American Academy, and I, decided to try and walk into the hole and see if we could find a pathway leading back to the ancient part of the sewer. It must still be under there somewhere.

The passageway we chose appeared to manage overflow from the city’s drainage system.

Getting in required us to pull back a heavy grate. “We should get someone else from the Academy to come help us pull back the grate.” said Matt.

“I don’t think anyone else from the Academy would want to come down here.” I said.

We slipped through the grate,

and entered the Roman sewer.

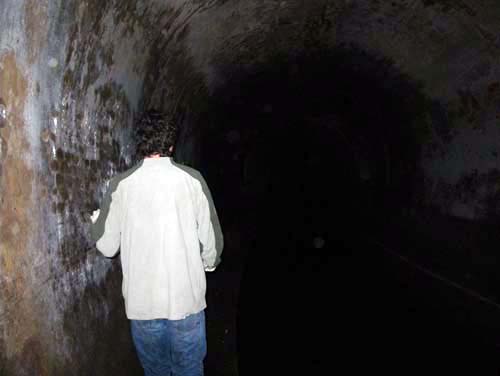

The tunnel led away from the river for a while,

and then seemed to be curving back to the North.

We could see light coming up ahead.

A huge room with a tunnel bisecting it halfway up. I felt tiny in the room, and was washed in panic as I imagined a giant waterfall of sewage surging over the curved stone.

Small ladders went up the sides of the chamber.

We put on latex gloves,

and started to climb.

“All clear.” said Matt.

As I climbed, I peered into the upper tunnel. I could hear water rushing inside.

Somewhere in there, a huge amount of water was passing by.

When we climbed out, we found ourselves in a room on street level. All around were the workings of a levy system that manages the sewer overflow.

Huge cranks and gears to lower giant metal walls.

You wouldn’t want to be down there, on the wrong side of the wall, during a flood.

Far below we could see water running: a tunnel, perpendicular to the direction that we just came. There appeared to be a small walkway on the side of the passage. We thought it might lead back to the ancient part of the sewer.

We climbed down and started to walk along.

The water flowing past was green.

The air was thick and humid.

We passed something that looked old. This stone arch might have been part of the ancient Cloaca.

A little way up, there was a brick hole.

We slid into it and came to a long brick tunnel. It didn’t seem that old to us, but our friend John Hopkins told us later that the large flat bricks we saw in the tunnel could be ancient.

At the end of the tunnel there were a few things, blocked off holes and entrances to other spaces. Matt fit himself through a small hole.

“Dead end.” he said.

We had gone to the end of every tunnel we could reach.

“We have to come back with a boat or a plank or something to cross the water.” said Matt. The idea of stepping out over the rushing sewer made my heart sink. “Or we could try and get permission to get into the excavated part of Cloaca.” I thought.

Walking back Matt found a spider in his shirt that had hitched a ride out of the sewer. It was probably the first time it had ever seen daylight.

↑ Return to Top of Page ↑